Scattered Light

This is the first of two blog posts that will be produced as a part of the Scattered Light commission consortium. In this entry, I give some background on the works of Dana Gioia, our collaborative relationship, and the beginnings of my new piece “The Burning Ladder.”

The story of my new piece for this consortium, “The Burning Ladder,” begins back in 2011 when I met poet Dana Gioia through his close friendship with my USC professor, Morten Lauridsen, and as a professor himself teaching courses on poetry and arts leadership. I took his Modern American Poetry course in fall 2011, which broadened my poetic horizons just as I was beginning to plan my final recital and see a musical future for myself beyond USC. I wrote The Lost Garden song cycle on four of Dana’s poems over the course of the next year, which helped me begin defining my musical style and composing process. I was fortunate to find a collaborator with a writing style that brings out some of the best in me.

Many of Dana’s poems grow out of specific classical forms or rhyme schemes that are not often seen in works of living poets. These techniques combined with his artful and skillful use of language give much of his work a certain dramatic flair. There’s a lot of pretense in his work, in a good way – pretension allows us to step outside of ourselves for a moment and elevate everyday occurrences artistically.

One of my favorite examples is “The Angel with the Broken Wing,” which I set last year. This is a blatantly strophic poem, yet it does not feel constrained by the verses – instead, the form and the language of the poem elevate the story of an inanimate object relegated to a gallery back room. Even more distinct is his ability to dramatize internal thoughts and conflicts, often with a good deal of irony or self-deprecation, as in “Interrogations at Noon.” The rhyme and rhythm of this poem is so tightly controlled, as if it were a verse from hundreds of years ago, and yet the sneering voice personifying anxiety and inadequacy in the poem is clearly the product of a contemporary mind. He writes with more freedom and grit in his voice at times as well, though with the same sense of lyricism and artistic choice of words; often times these poems tend to describe natural landscapes and pure aesthetic beauty instead of human stories and thoughts.

The balance of classic techniques and lyricism with modern imagery in Dana’s work keeps me coming back to it. It gives many of his poems the rare distinction of being ideal for choral settings in their length (not too short, not too long), style of prose (musical, but with room for more music), and thematic content (universal enough in to be sung by a large group). This is a thin line to walk. Finding texts that fit whatever we are looking for on a particular project can be one of our biggest challenges. Due to these difficulties, in my opinion, choral composers occasionally default to the use of texts which fit these criteria *so* well that they can come across as a bit generic. Dana’s poetry sets brilliantly and fluidly, and yet there is nothing generic about it.

As I did with “The Angel with the Broken Wing,” I have chosen a text which poses some challenges in a choral setting, largely due to its highly specific narrative story. However, it is quite different from the other poems I have mentioned here in its execution.

The Burning Ladder

The story of Jacob’s ladder comes from the book of Genesis, Chapter 28:

10 Jacob left Beersheba and set out for Harran. 11 When he reached a certain place, he stopped for the night because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones there, he put it under his head and lay down to sleep. 12 He had a dream in which he saw a stairway resting on the earth, with its top reaching to heaven, and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it. 13 There above it stood the Lord, and he said: “I am the Lord, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac. I will give you and your descendants the land on which you are lying. 14 Your descendants will be like the dust of the earth, and you will spread out to the west and to the east, to the north and to the south. All peoples on earth will be blessed through you and your offspring. 15 I am with you and will watch over you wherever you go, and I will bring you back to this land. I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.”

16 When Jacob awoke from his sleep, he thought, “Surely the Lord is in this place, and I was not aware of it.” 17 He was afraid and said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God; this is the gate of heaven.”

This vivid story has been re-told, re-interpreted, and depicted artistically in many ways. Biblical scholars throughout history have speculated on its metaphorical intent. The most straightforward reading of the story clearly shows some sort of strengthening of the connection between heaven and earth. Some believe that the ladder represents the exiles that the Jewish people would endure before the coming of the Messiah, especially since the angels are seen ascending and descending or falling back down the ladder.

Dana gives us a completely different take on Jacob’s vision in “The Burning Ladder.” Here he joins countless artists over the centuries who have re-interpreted and re-purposed images or stories from the Bible, using their familiarity as cultural touchstones for many people while adding new commentary or subverting original their religious meaning. The poem seems to ask why Jacob does not ascend the ladder himself, escaping the trappings of his earthly life while he has the chance – perhaps due to some sort of weakness of character or fear of change. He narrates this in the third person, allowing for a certain objectivity and judgement of Jacob’s perceived failings.

The poem only contains two sentences, one declaration of the poem’s intent and one spiraling run-on describing the Jacob’s vision and his intransigent response. Despite the continuous flow of these phrases, they are broken up into short lines on the page with a large indent at every “verse,” giving the impression of a winding, unstable ladder. Despite the movement on the page, the urgency of the storytelling, and the vivid imagery of light and flames, Jacob still stays resting on the cold ground. Inertia wins out here. While I don’t consider myself a person who shies away from change (I did run off to Scotland, after all), I have certainly felt “sick of travelling” more than my fair share in recent years of living abroad and recent months of frequent short trips. I couldn’t help but let this line strike me in this context.

Many things must be taken into consideration when setting a text to music. I want all of the nuances of Dana’s poem to come across in the music somehow, but literary devices don’t translate directly into music. For instance, how can I musically convey the feeling that the line breaks and indenting create in the poem? When read off the page, this effect does not necessarily come through. It takes time to absorb the words’ concrete meanings and shades of subtext thoroughly enough to find answers to these kinds of questions intuitively. I knew from early on that the answer to this issue would hold the key to the form and pacing of the piece.

One of the very first things one must think about when writing music to pre-existing text is the rhythm, since the words already have syllabic rhythm themselves. When I consider what rhythms I will be using in a new piece, I immediately contemplate texture as well. Musical texture is the result of the interaction of different rhythms in different vocal parts, so I see rhythm and texture as inseparable. Greater rhythmic differences between voices or instruments in a passage result in more complex, dense, or chaotic textures.

While intricate or chaotic textures crop up frequently in my music, my other settings of Dana’s poetry helped me find ways of stripping this part of my style down a bit, letting the words shine through without much density or rhythmic layering. This poem calls for something a bit different:

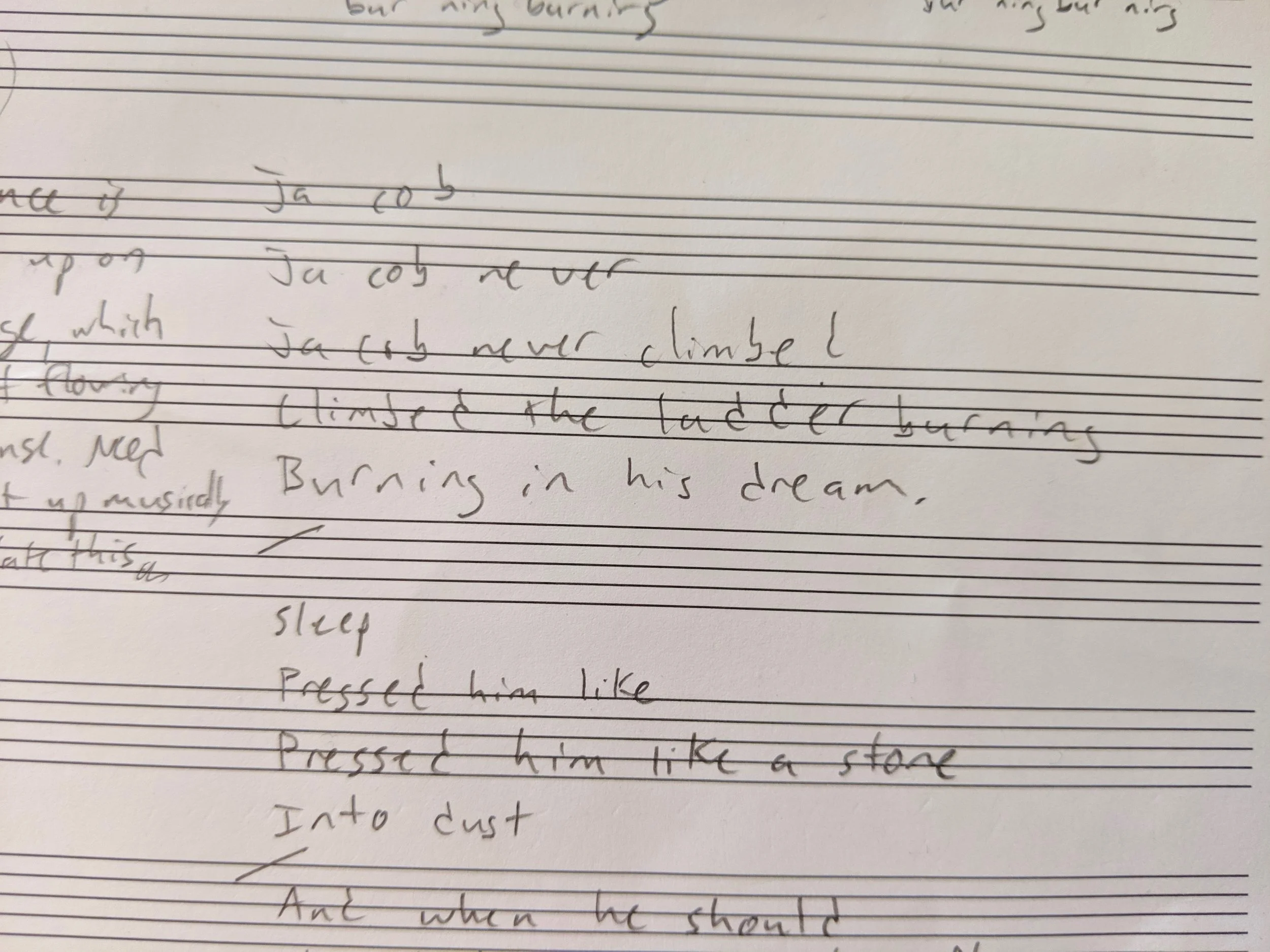

I quickly determined that the urgency and continuous nature of the poem calls for quick, fiery rhythms and the dense textures that will result from layering these on top of one another. In order to do this, I’ll need to repeat some words. By breaking up the phrases unevenly as I’ve shown in this sketch and repeating the words within these broken phrases, I can recreate the impression of the lines on the page through the music.

Pacing out the text in this way turns the words into building blocks I can use to create rhythmic repetition, beginning simply and building up to faster note values. The rhythmic collisions between the voices will give the music the fiery sound that this poem deserves.

How is this going to play out over the course of the entire piece? I know that pacing is going to be very important, as I said earlier. If I let these rhythms repeat throughout in one long string throughout the piece, as in a more minimalist work, they will lose their power to create drama. These rhythms will have to stop, start, change and grow judiciously over the course of the piece in order to keep the tension between the ladder to heaven and Jacob’s inertia alive.

Next week, I will share with you how these ideas also inspired the harmonies I use in The Burning Ladder, and how the harmonies and the rhythms join together to create a work that I hope has as much fire as the poem!